15th March 2021

A voices blog by Alison Morton, Acting Executive Director, Institute of Health Visiting.

Over the last few weeks social media has been very active, with discussions on whether it is safe to carry out health visiting universal health reviews over the phone, or by video, in the absence of a face-to-face option?

As expected, there are a range of views and it is definitely a question that requires a rigorous answer. Our role at the iHV is to support a learning culture, rather than one driven by blame. So, before I start with our list of important considerations, I thought I would set out our starting place…

Alison Morton, Acting Executive Director, iHV

We know that it has been really tough being a health visitor, or a health visitor manager, or a commissioner of health visiting services, during the pandemic. Thank you to everyone working to support families at this time. As the world “stopped”, babies have kept on being born (in fact 600,000 babies have been born in the pandemic so far) and the normal struggles of parenthood have been amplified by the secondary impacts of lockdown. Need has soared. Parents and carers have been struggling with loneliness, increased anxiety and depression, feeling “locked in” which has been particularly difficult for those in cramped and inadequate accommodation, and many families have been tipped into vulnerability and poverty. For some families, home has not been a safe place as rates of domestic abuse, serious incidences involving babies and young children, and child maltreatment, have sadly increased[1].

Health visiting entered the pandemic in an already depleted state[2]; within this bleak context, health visitors have gone “above and beyond” to support families and protect vulnerable babies and young children[3]. We are proud of the multitude of good practice examples that we have seen – we know that the HV service has made a massive difference in so many ways. Our thoughts that follow are therefore not intended to be a criticism, but rather the start of an informed debate on the next steps.

What can we learn from the service “workarounds”? by definition, they were developed very quickly and are currently untested.

The best place to start is to have the intended outcome in mind – the Healthy Child Programme (HCP) is a universal programme of support for all families which aims to improve outcomes for children and reduce inequalities. To achieve this aim, one important function of the HCP is to identify those babies and young children who are at risk of poor outcomes… and do something about it. This includes the often-overlooked function of eliciting need and brokering engagement in support.

What does the evidence tell us? It is clear that:

- There are a multitude of reasons why parents who need support the most are the least likely to ask for it, or engage in it – they may feel stigma and shame, or not recognise that they have a “need”, and many tell us that they are afraid that people will think they are a “bad” parent (whatever that means) or take their child into care.

- A sensitive, strengths-based, personalised approach is the most effective[4] [5] and acceptable[6] way of eliciting need and brokering engagement in interventions to make the difference[7].

- We can have the best interventions in the world, the best “tick box assessment forms”, but if need is not volunteered or elicited, the babies, children and families who need this support will remain hidden[8], and our efforts are rendered useless.

- We need to get this right, as we have well documented widening inequalities in this country and some of the worst outcomes for a range of indicators[9] when compared to statistically matched countries.

What needs are we specifically trying to address?

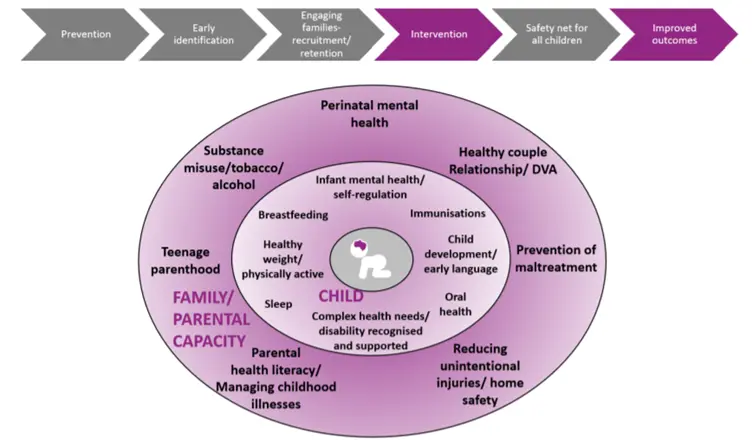

The answer is, “quite a few”. The unique selling point of the health visitor is that they provide the only universal service which straddles a breadth of clinical, child development and statutory vulnerabilities[10], as well as those linked to the wider determinants of health. These are set out in the image below:

Are telephone or virtual contacts a safe and effective way of completing a holistic health and vulnerability assessment for such a breadth of needs (these are completed at each of the 5 mandated contacts)?

All children aged 0-5 in England should receive a minimum of 5 mandated reviews (other UK countries offer many more). These contacts are important as they provide a vital safety-net for vulnerable babies and young children. They are their opportunity to “be seen” by a professional with the right skills to identify their needs and ensure their protection if they are vulnerable. By comparison, older children at school will be seen by a qualified teacher every day that they are in school from the age of 5 until they leave school – younger children do not have this safety net. Let’s put this into perspective – making sure that these 5 contacts are effective is surely not too much to expect – it is such a minimal ask, with a relatively small cost?

The iHV has previously questioned whether the drive to achieve KPIs to evidence the delivery of the 5 mandated contacts has inadvertently led to a race to the bottom which has resulted in us being satisfied with “Ticking the box, but missing the point”? Is that really good enough?

But non-face-to-face contacts are very efficient, we’re told. However, it is possible to deliver an efficient service which at the same time is also ineffective – we’ve written previously about this in relation to developmental reviews based solely on postal Ages and Stages questionnaires. You get what you measure – a beautifully filled in tick box, rather than a validated holistic assessment of the child and family’s breadth of needs. What we really need to know is, “Did we find the children that were at the greatest risk of poor outcomes? Did we make a difference to their outcomes?” And the most important measure, “Did we reduce inequalities?”

Anecdotal evidence suggests that virtual contacts do have a place– some families have found video contacts extremely helpful during lockdown. For transactional conversations involving “advice giving” for issues like breastfeeding support, or managing minor illnesses, they have been invaluable and will no doubt become an important part of “business as usual” after the pandemic.

However, significant concerns have been raised about their use in identifying vulnerabilities like domestic abuse, mental health problems and child safeguarding concerns[11]. We know that we already have a problem in this country with vulnerable children being hidden from support services, and the pandemic will have exacerbated this; the total number of serious incident notifications for children during the first half of 2020-21 increased by 27% on the same period in 2019-20 – of these, 35.8% relate to under 1s who remain at the highest risk of homicide than any other age group[12].

It is likely that virtual contacts have limited use for eliciting vulnerability and managing sensitive issues and can only ever be second best to face-to-face consultations. It’s very difficult to ascertain what else specifically might be going on in a home, for example whether there is domestic abuse, from a video consultation. Or indeed complete the unique health visitor holistic assessment which may identify a range of different factors which co-exist, and collectively impact on, the baby or young child’s wellbeing. Health visitors will also be assessing for clinical vulnerability. How do we assess a baby adequately? It is clearly impossible to weigh them and measure their head circumference and length, review their skin integrity for bruising, or assess their muscle tone in a video call. Late diagnosis is a widespread problem for many neuro-developmental conditions[13] like cerebral palsy and Spinal Muscular Atrophy in the UK. We need to do better, not worse.

Current research on the use of video-consultations in healthcare has been conducted with purposefully designed GP or hospital services, and evaluated with patients who have an identified “problem” and the economic and technological capacity to choose to use this approach. Some of the most vulnerable families may not have access to phone credit or Wi fi, making calls or video contacts impossible and putting their children at enhanced risk and greater disadvantage.

Findings from Jane Barlow’s research into health visiting during COVID and the use of virtual visits reported,

“a range of pandemic-related issues that were specific to the problems caused by the social distancing requirement, were perceived to have impacted the ability of practitioners to safeguard vulnerable children, thereby rendering them ‘invisible’, including: the requirement to conduct virtual visits … which significantly hindered their ability to safeguard vulnerable children due to its limitations in terms of actually seeing and assessing the children in person”.

So in conclusion, as a temporary “service workaround” during lockdown, virtual contacts have been “better than nothing”, and they have a place in meeting the needs of some families, some of the time. However we are very concerned by emerging reports that they may become “business as usual” for delivery of the mandated health reviews, even when the restrictions are lifted. We would not normally accommodate such a significant change to a service delivery model without robust evidence of safety and effectiveness, not least an evaluation of the risks and whether the intervention might actually cause harm. Further research is urgently needed to inform the implementation of virtual contacts in health visiting.

We need to understand how virtual contacts can be used safely – who they work for, when and how?

In the meantime, let’s get back to what we know works as quickly as possible. At the iHV we cannot support the wholesale replacement of face-to-face mandated contacts with virtual contacts. From the evidence that is currently available, this approach would increase risks and the likelihood that vulnerable families and children will fall through the gaps between services, which is highlighted as a significant risk factor in almost all Serious Case Reviews[14].

In our view, the untested “COVID workarounds” of virtual contacts are a smokescreen which detracts from the much bigger underlying issues that are driving their introduction in practice.

We do not have enough health visitors or resource within the 0-5 Public Health Grant to deliver the Healthy Child Programme in full, in the way it was intended.

Until this is acknowledged and addressed, we are moving the deckchairs on the Titanic and will remain disappointed that we do not achieve the outcomes that we hoped for – we need to keep our eyes fixed on where we hope to be heading, with our aim to improve outcomes for children and reduce inequalities.

If you agree, join with us and speak up about this – otherwise our babies, children and families will be left “Zooming in but missing out” and they deserve better.

Alison Morton, Acting Executive Director, Institute of Health Visiting

References

[1] Blackwell A (2020) ‘Covid pressure cooker’ behind 20% rise in reports of serious harm to babies, says inspectorate head. Community Care. https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2020/11/10/covid-pressure-cooker-behind-20-rise-reports-serious-harm-babies-says-ofsted-head/

[2] Institute of Health Visiting (2020) State of Health Visiting in England. https://ihv.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/State-of-Health-Visiting-survey-2020-FINAL-VERSION-18.12.20.pdf

[3] Conti G (2020) The impacts of COVID-19onHealth Visiting Services in England: FOI Evidence for the First Wave https://www.dropbox.com/s/o2hldoyfbn7rmpb/The%20impacts%20of%20COVID-19%20on%20Health%20Visiting%20in%20England%20-%20Redeployment%20Brief%20211220%20POSTED.pdf?dl=0

[4] Davis H, Day C (2010) Working in Partnership: The Family Partnership Model. Pearson, London.

[5] Robling M, Lugg-Widger F, Cannings-John R, Sanders J, Angel L, Channon S, et al. (2021) The Family Nurse Partnership to reduce maltreatment and improve child health and development in young children: the BB:2 6 routine data-linkage follow-up to earlier RCT. Public Health Res 2021;9(2). https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/phr/phr09020#/abstract

[6] Morton A (2020) What do parents want from a health visiting service? Institute of Health Visiting, https://ihv.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HV-Vision-Channel-Mum-Study-FINAL-VERSION-24.1.20.pdf

[7] Cowley S, Whittaker K, Grigulis A, Malone M, Donetto S, Wood H, Morrow E & Maben J (2013) Why health visiting? A review of the literature about key health visitor interventions, processes and outcomes for children and families. National Nursing Research Unit, King’s College London. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/nmpc/research/nnru/publications/reports/why-health-visiting-nnru-report-12-02-2013.pdf

[8] Children’s Commissioner (2019) Childhood vulnerability in England. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/report/childhoodvulnerability-in-england-2019/

[9] RCPCH (2020) State of Child Health in the UK. https://stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk/

[10] Public Health England (2020) No child left behind: a public health informed approach to improving outcomes for vulnerable children. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vulnerability-in-childhood-a-public-health-informed-approach

[11] Barlow J (2020) The invisibility of infants and preschool children: Health visiting in the time of COVID. iHV Evidence Based Practice conference presentation.

[12] BETA: .GOV.UK (2021) Part 1 (April to September) 2020-21. Serious incident notifications https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/serious-incident-notifications

[13] Maitre, N.L., et al., Network Implementation of Guideline for Early Detection Decreases Age at Cerebral Palsy Diagnosis. Pediatrics, 2020. 145(5).

[14] NSPCC – national repository of Serious Case Reviews. https://library.nspcc.org.uk/HeritageScripts/Hapi.dll/search2?&LabelText=Case%20review&searchterm=*&Fields=@&Media=SCR&Bool=AND&