21st August 2017

In support of Health Visiting Week (#HVWeek), and with today’s theme being around Safeguarding, a blog by one of our Fellows, Helen Mulleady.

Helen Mulleady, FiHV

Neglect is the most common form of maltreatment of children (Child protection register and plan statistics for all UK nations 2016). Its origins can be due to a variety of reasons, from inability to parent through to knowing how to parent, attachment disorder or mental illness and/or social issues, such as domestic abuse. In these cases, a child protection plan is put in place by the local safeguarding team, normally when the threshold has been exceeded along with consensuses from the multi-agency professionals agreeing that a child is more likely to be harmed unless intervention is instigated. Timescales and targets are set, to ensure that the child is protected from additional harm should parents/guardians be unable to make or sustain the desired changes.

The family that I was involved with was coming to the end of the timescales and had been informed by the Independent Reviewing Officer (IRO) that they would be given an additional six months to sustain a change or legal proceedings would be instigated by the Local Authority. The family at this time also moved to a property within my geographical caseload area, immediately after the outcome of the reviewing case conference.

Following evaluation of the previous health visitor’s records and child protection plan, it was apparent that the main concerns were around the mother’s attachment to her second child, day-to-day care of the children, and keeping health appointments. In addition, both parents seemed to have experienced, in their own upbringing, periods of sub-optimal parenting that manifested itself in poor school attendance and not achieving any educational qualifications. The summary from the parenting assessment concluded that Mother did have the potential to become an adequate parent. Children services had provided the parents with extensive support around day-to day-care of the children and home environment; however the desired outcome had not been achieved.

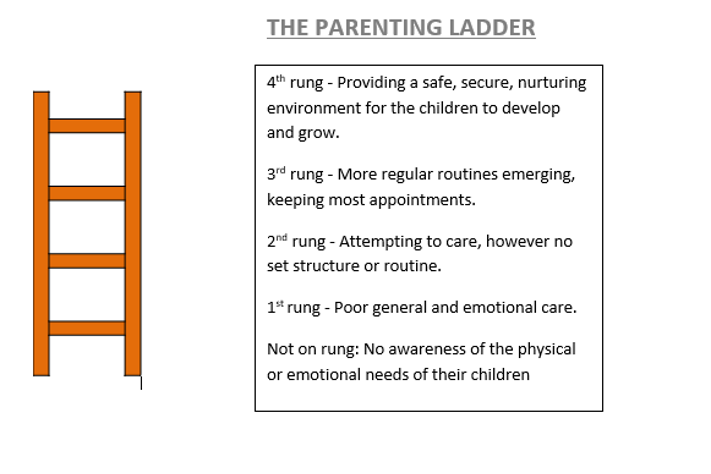

Knowing I had a defined time limit, I needed to ensure that the parents fully understood the safeguarding process and to appreciate their lack of progress in their parenting, and the likely consequences if no improvement occurred. It was essential that all my contacts were based on influencing a change in the parents’ behaviour by encouraging them to take a reflective stance in how their children were feeling (Underdown, A. 2013). Naturally, these types of assessments are individually based; the level of guidance needed varies from client to client. In this case, I felt it was essential to produce a prescriptive plan (action envelopes) until parents had established a strong healthy template of good parenting. The eventual goal being to empower them to instinctively meet their children’s needs. From my analysis of the parents, I concluded that a visual model of good parenting was required, this subsequently lead to the creation of “The Parenting Ladder”.

Parenting Ladder

The essence of The Parenting Ladder provided the parents with visual cues to enable them to identify the direction they needed to take, by providing them with the opportunity to self-evaluate and self-motivate. The action envelopes included activities that they would promise their children to carry out over the coming month.

This approach drove the parents to integrate changes in their behaviour that generated pride and satisfaction upon completion. The activities were all linked to improving health and wellbeing, which were aligned to the child protection plan. Using a scrap book for the parents to record the activities appeared to be key in unleashing and articulating their emotions towards their children. By reflecting with parents and more especially with the mother, she began to develop an understanding of her children’s emotional needs and began to feel comfortable in her responses to them. She became more tactile towards both boys, especially the second, and would spontaneously hug him or sit him on her lap during my visits. On my first visit following the introduction of the programme, a family photograph had been attached in the scrap book, which gave the mother the opportunity to express what her family meant to her and, I believe, was one of the sparks that promoted changes.

Progress continued, at the third contact a noticeable improvement in the home environment was evident; this was affirmed by their social worker. Reports from the nursery also indicated positive improvements in the children’s attendance, presentation and behaviour.

At the review conference, the child protection plan was de-escalated to a “child in need status”.

Both children are now at school. The parents have a new addition to the family. This infant is receiving treatment for a health condition (not life-threatening) which has required weekly appointments at a hospital twenty miles from their home. These appointments have been kept. Furthermore, the mother has had confidence to join an online forum regarding the baby’s condition; this has enabled her to discuss/recommend suggestions that have been incorporated into a care plan.

In view of these improvements the level of health visiting support was downgraded to universal services (HCP 2011). From time to time I receive a text message from the mother requesting some health advice.

Creation and use of the “parenting Ladder” demonstrates that health visitors are needed to support families, to be able to be mobile in our thinking and creativity in order that we can provided bespoke care plans for families.