24th September 2021

In support of the #TurnOffTheTaps #InvestInHealthVisiting campaign, we are delighted to share a Voices blog by Toby Lowe, Visiting Professor of Public Management at the Centre for Public Impact, on how health visiting creates positive outcomes.

Toby Lowe, Visiting Professor of Public Management at the Centre for Public ImpactIt is near universally accepted in the UK that the purpose of public service is to help people create positive outcomes in their lives. It’s pretty hard to find anyone who fundamentally disagrees with this position.

If this is the case, then it follows that public service should be organised and resourced to give it the best chance of helping to create these positive outcomes, right?

What would that look like? We can explore this by looking at the example of Health Visiting (as I’ve recently been exploring exactly this question with Alison Morton, Executive Director of the Institute of Health Visiting)

How is an outcome made?

Factors that create an outcome

Let’s start with a simple question: how is an outcome made? And let’s make this specific: what are the outcomes supported by Health Visiting, and how are they made?

Previous reports on the work of Health Visiting help identify a range of outcomes which Health Visitors seek to support. They list a range of outcomes, including “maternal mental health” and “health, wellbeing and development of the child”. Let’s pick the latter of these as the most obvious to explore: how is the outcome of “health, wellbeing and development of the child” actually created?

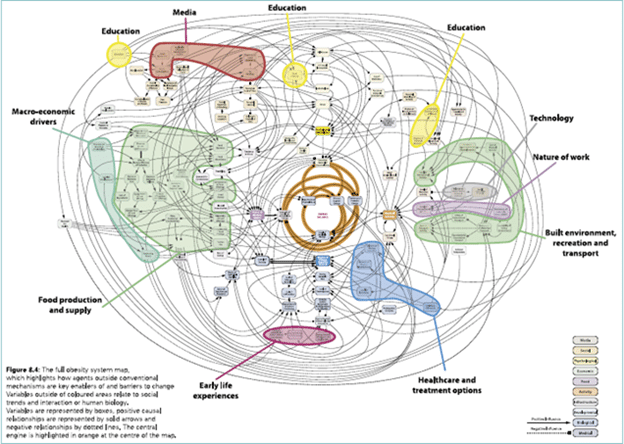

What public service calls “an outcome”, like child wellbeing, is simply a snapshot of that child’s life at any particular point in time. Whether a child experiences “wellbeing” (or not) is the interaction of hundreds of different factors in that child’s life. We can see this clearly from research into the outcome of obesity. Researchers sought to find out all the factors which contributed to a person being obese or not. They were able to identify 108 different factors, and also the relationships between those different factors. They represented those factors, and their relationships, in a systems map of obesity.

The individual factors that create the outcome of obesity are too small to see on this diagram, but you can see them summed up in areas like “food production and supply”, “education”, “media”, “the nature of work”, “the built environment” and “healthcare and treatment options”.

We see from this that the outcome of obesity is the product of a whole system – of all of these different factors interacting in a person’s life.

If we apply this knowledge to the outcome of “child wellbeing” we can identify the likely factors which create wellbeing, or its absence – from good nutrition, through to green spaces, and including other things like maternal mental health, income availability, and access to healthcare services.

This shows us the constituent parts of how an outcome is made – the factors that create it. But there is still one more thing to consider – the actors that create an outcome, the people and organisations who make things happen.

Actors that create an outcome

It is important to consider the actors who create an outcome because one of the other key messages from research in this area is that outcomes (what they mean and how they are made) are subjective: for example, most children’s wellbeing would be enhanced by seeing more of their families. For other children, contact with their family is a terrible idea. This is another way of saying that the complex system that creates an outcome in our lives is unique to us. In fact, the most accurate way to say this is that it is the unique complex system that is our lives which creates an outcome. It is all the actors that are unique to us (starting with us) and all the factors that are uniquely felt through the subjectivity of our own lives that create an outcome.

We can thus represent the actors and factors which create the outcome of wellbeing as a solar system, with ourselves at the centre.

Now we know how an outcome is made, what does that tell us about how Health Visiting should be organised so that it enables the production of those outcomes?

Learning as strategy

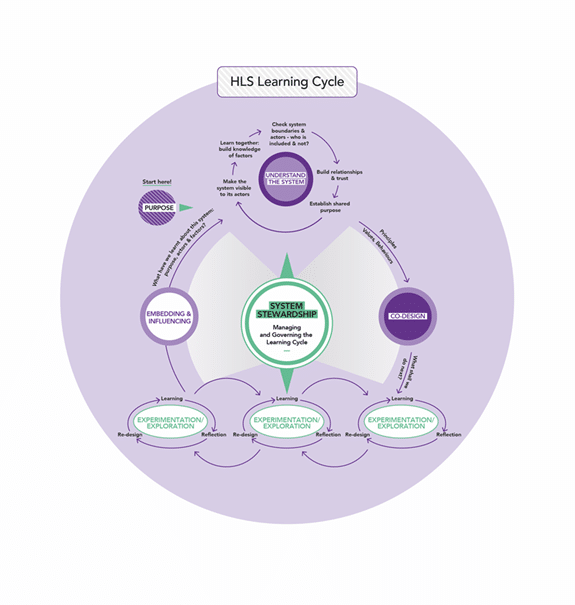

Through working with a range of public services across the world, we have seen how the role of public servants can be framed so as to maximise the chance of creating a positive outcome, whilst also maximising public service efficiency.

Essentially, learning is the strategy for public servants to help people create positive outcomes. And that learning strategy begins with the relationship between a Health Visitor and the family they serve.

What we have seen is that public servants, such as Health Visitors, form a learning relationship with the families they serve as the mechanism to help those people create positive outcomes in their lives.

This learning relationship begins with the public servant forming a relationship of trust with those they serve. They use that trust to work with families to explore their ‘life as system’ – to understand the actors and factors that lead it to create the outcomes that currently exist in that person’s life. What are the things that promote wellbeing for your children (rather than children in the abstract)? And what are the things that get in the way of wellbeing for your children?

The next part of the learning relationship is co-design work – they work with the families they serve to design experiments and explorations which try out different things to see what helps produce different outcomes. What happens if we try this? (Crucially, these experiments explore both personal and structural factors – from “let’s explore doing mealtimes differently” to “are you getting the benefits to which you’re entitled?” and “can we help get those creditors off your back?”

The results of all of these experiments and explorations create change in that person’s life as system. This is the process of how outcomes are made in real life. They are unique and personal to each person’s life as system.

Health Visitors as infrastructure for outcomes

And that means if we want positive outcomes, we need to invest in the infrastructure by which such outcomes are made – public facing workers who can build these learning relationships with those that they serve. Without such public facing workers, we cannot expect positive outcomes. Investing in Health Visitors as the basic infrastructure which enables outcomes to be made, and managing them so that learning is both their strategy, and the management strategy of their organisations and places, is how we can create positive outcomes for families.

If you ask the question: “what outcomes do (workers like) Health Visitors deliver?” you’re asking the wrong question. No public service, or any other form of civil society organisation, “delivers” outcomes. Outcomes are made in the unique life systems of each and every person, interdependently. You can no more isolate the contribution of Health Visitors to creating family outcomes than you can isolate the contribution of clean water to a healthy ecosystem.

The useful view – based on our understanding of how outcomes are really made, is to view workers like Health Visitors as the infrastructure on which any form of positive outcomes depend. Like the infrastructure which gives us access to clean water, think how much harder (and wasteful) it is to try and create positive family outcomes without people whose job it is to have a strong relationship of trust with each and every family, so that they know the unique context of each and every life, and who can learn together with those families. If those learning relationships don’t exist, then a positive outcome for every family is just wishful thinking.

Toby Lowe, Visiting Professor of Public Management at the Centre for Public Impact

Twitter: @tobyjlowe

#TurnOffTheTaps Campaign needs you

Join the campaign and share your stories on how you made a difference to babies, children and family’s lives. You can quote how health visitors are a vital part of the health workforce who provide an infrastructure of support for physical health, mental health and social needs. Let’s make sure all families get the help and support they need, when they need it.