16th February 2021

A Voices blog by Debbie Fawcett and Nicola Ford, Specialist health visitors, Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust (CLCH) on supporting homeless families and digital connections.

COVID-19 has presented many challenges to the population as a whole, with the negative impact felt the hardest by groups that were already disadvantaged, like homeless families.

As specialist health visitors for homeless families, we support families (0-19 years) living in various temporary accommodation settings, including bed & breakfast, women’s refuges and blocks of multiple units. Wi-Fi internet access is not always available in temporary accommodation, so tenants must purchase data packages through mobile phone providers to access the internet, or alternatively access the internet via public Wi-Fi hotspots and libraries.

During the first lockdown in 2020 many services suspended face-to-face contact, rapidly transferring to an online presence and creating an instant barrier to accessibility for some families. For example, 111 received a high number of calls regarding COVID-19 and callers were advised to seek information online to avoid lengthy call waiting time. Suddenly going online was the only way to access information and services including: housing advice, benefit claims, shopping, medical appointments etc. The Children’s Commissioner (18/8/20) estimated that ‘9% of families in the UK do not have a laptop, desktop or tablet at home’. The digital divide will again have a significant impact on children’s education and long-term achievement.

The health visiting service also adjusted to lockdown, transferring from face-to-face consultations to telephone or virtual contact. Unable to access the social networks online, maintaining health visitor visibility at the accommodation units continued throughout the lockdown as an important way to support families. Homeless families lacked the ability to easily access up-to-date COVID-19 information online. To address this, we telephoned clients and distributed information which included translated leaflets by Doctors of the World (2020).

The challenges of home schooling are exacerbated when a family lives in a self-contained, open-plan studio flat or one room, and share a kitchen and bathroom with other residents. There is no quiet space or privacy for the child; no room for a desk or storage for books and no online resources.

In March 2020, a supermarket offered to donate smart phones, with preloaded SIM cards, to the local MP for distribution to ‘vulnerable families’. After presenting the offer to our managers, it was agreed we could receive 100 iPhones to distribute. Identified from our caseload knowledge, priority was given to families with primary school children and those with no devices in a household.

A letter (including details of the donation, 3-month SIM package and link to resources) was given with every mobile phone, asking for the data to be used to support their family’s health and education. Distribution was made to each accommodation, via door step visits (wearing PPE) to allow for a verbal explanation, and an adult was asked to sign a slip to confirm receipt. No details were shared with the supermarket but a record kept of family and allocated telephone number. To maximise the digital opportunity, parents needed to have computer literacy skills to be able to research and access sites, create a Wi-Fi hot spot and ensure internet safety. Despite directing the recipients to the supermarket for technical support, we received regular queries and requests for help to support digital literacy. In response to us raising technical issues, the original 3-month data package was extended a further 3 months by the provider, although families kept the smart phone.

After the initial distribution to families in temporary accommodation, we offered the remaining devices to other families nominated by our colleagues in school nursing, health visiting and children’s therapies. Initial responses from our colleagues were based on vulnerability as categorised by a child protection or child in need plan, so our criteria was restated to ‘where the professional recognised vulnerability and the smart phone with preloaded data would make a positive difference’. Whilst the devices were given to support family health and their access to education, it became clear through feedback that there were wider benefits.

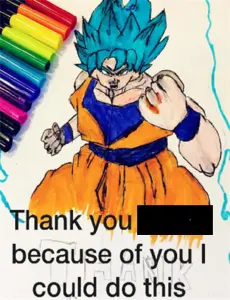

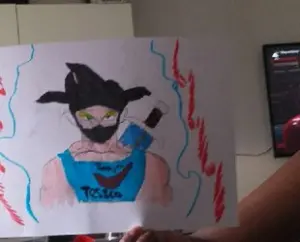

Children and parents were excited and thankful. We received texts and pictures for several weeks after, as well as stories of the difference the phone had made.

- Children were able to access new and interactive educational resources, such as BBC Bitesize, and parents reported they were more engaged in their learning.

- Families were able to access virtual health appointments.

- One family used the device to access hospital and portage appointments, as well as specialist educational resources and a parents’ support network.

- School nurses offered additional support during school closure and reported that teens appeared more comfortable and open in the virtual arena.

- During lockdown there was a significant rise in domestic abuse incidents (Office of National Statistics, ONS, 2020) – the donated phone enabled one victim to have safe communication, empowering them to seek advice regarding domestic abuse.

- The phones created opportunities for social connection, supporting mental wellbeing.

- A clinically extremely vulnerable child in year 6, was able to say goodbye and hello to classmates, reducing anxiety for the transfer to high school.

- The phones also reduced the perceived stigma of poverty and homelessness, demonstrated through feedback from a year 10 pupil who reported that they could now access social media as well as catch up with home studies.

This experience highlighted the assumptions that professionals can make regarding a client’s internet access and their computer literacy. Most adults have a mobile phone, but access to adequate data when broadband is not available means monthly contracts, or the most expensive option, pay as you go. Services need to consider all service users when moving online. Families may also feel excluded by perceived shame regarding their studio flat or lacking suitable toys to join in online activities.

The specialist health visiting team has continued to visit families living in temporary accommodation, offering continuity throughout the pandemic. We advocate strongly for clients, using our knowledge of the families and their home circumstances.

The Government revised guidance 31/12/20 (Gov.co.uk 2020) on access to vulnerable school places includes additional categories of ‘those living in temporary accommodation’ and ‘those who may have difficulty engaging with remote education at home (for example due to a lack of devices or quiet space to study)’. Health visitors are well placed to ensure that those already facing disadvantage in their learning are not put at an even greater disadvantage through the pandemic.