4th April 2017

The second in a series of blogs by Dr Robert Nettleton, Education Advisor, Institute of Health Visiting, on his travels to Cape Town, South Africa through his Florence Nightingale Foundation Travel Scholarship 2017.

Robert is keeping us up to date with his travels and professional visits through regular Voices blogs – Read the blog from his first week

This week I’ve been having opportunities to connect further with leaders at the centre of bringing hope, help and healing to the experience of multi-layered trauma, while working up-stream to re-energise preventative child and family public health focused on the first 1000 days.

Lane Benjamin – trauma-informed approaches

Lane Benjamin is a clinical psychologist for whom ‘trauma-informed approaches’ are key to unlocking hope, help and healing at individual, community and societal levels. In her research, she delineates ‘continuous trauma’ as a distinct sub-category of post traumatic distress syndrome. The distinctive historical trajectory of South Africa means that she sees that the whole of society as well as individuals are exposed to trauma at multiple levels and on a more or less continuous basis. As health visitors, we are familiar with the notion of toxic stress, its impact on brain development, social and emotional development and lifelong health outcomes sensitive to Adverse Childhood Experiences. We are less familiar with this as systemic within society.

Lane has pioneered the application of this perspective through CASE (Community Action towards a Safer Environment) where she particularly worked with youth. She is now increasingly shifting her focus to the first 1000 days as formative. She is an Advisory Board member for Cape Town’s Perinatal Mental Health Project. The connection between a ‘trauma-informed’ approach and infant and perinatal mental health was obvious from my visit to the Perinatal Mental Health Project team at Mowbray Maternity Hospital, led by Simone Honikman. There is an ‘epidemic of mental distress among women living in adversity’. Alongside wealth, there are extensive townships or informal settlements that are a legacy of the apartheid era in which, for example, 50% of women are HIV positive and levels of domestic, gender-based and sexual violence are high, as is poverty. Providing for accessible front-line assessment of mental health distress is a priority, through providing training to a range of workers and also within the community through ‘social connectors’ (I’ll learn about this more next week). A challenge that resonated for me was about promoting quality and consistency in a fragmented system where there is also a heavy reliance on separate NPOs (not-for-profits) as providers of services.

Two key learnings for me were:

- The importance of what Simone calls ‘self-care’ – what we might call supervision with a substantial restorative component. I met, briefly, Charlotte who provides counselling out of a cubby-hole of an office in a maternity hospital. Her heart was bigger than her office! Maintaining resilience is something that we know is important, and the ‘Sollihull Approach’, while not rolled out in Cape Town, was something that colleagues recognised as applicable.

- The dilemma of seeking to deliver a quality service within a very low-resource environment. This resonated with me as we face resource pressures in the UK. We discussed and reflected on what would be the essential elements of a service (the ‘active ingredients’ or ‘programme mechanisms’) and what could be delegated or substituted without placing effectiveness at risk. The ability to form effective empathic relationships is one of those essential elements common to both South Africa and the UK, as is support and supervision.

Parent, Infant and Child Health (PICH) Wellness Workgroup for the Western Cape Province

Also, this week, I was able to attend (and present to) a meeting of the Parent, Infant and Child Health (PICH) Wellness Workgroup for the Western Cape Province at the invitation of Dr Elmarie Malek. This group is strategic in scope and included some presentations from varied backgrounds, such as a trauma surgeon who, like so many HVs, looks ‘upstream’ to use data about injuries and mortality in childhood to develop strategies to improve safety. For example, trackers recording driver behaviour are supplied to taxi minibus drivers who can compete and be rewarded for improved safe driving behaviour, thus reducing the risk of injury to the many children who are on the roads unsupervised.

Discussion ranged over how the pattern of injuries reflect the interaction of children’s development and their environment. Education about this is one component but it needs to be matched by such interventions within the environment.

Again and again, the iHV Champions training model resonated with the South African context as we know that this supports local leadership to effect and sustain change and improvement.

Dr Maylene Shung-King

My last meeting this week was with Dr Maylene Shung-King, Senior Lecturer in the Health Policy and Systems Division, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Cape Town. Maylene has a particular interest in health systems, leadership and the school-age population. My conversation with her led to some pieces of the mosaic of impressions so far to link into place for me. She explained that the (very limited) school health service was picking up and seeking to mitigate health and developmental problems ‘missed’ in the pre-school age group. A brief history lesson was both illuminating, for understanding the present state of affairs, and instructive, for our own in the UK. In the 1940s, the then Minster of Health, Gluckman, developed a vision for health policy with a strong preventative and public health focus.

The Gluckman Commission (1942–44) was an attempt to redirect the health system. At the heart of this vision was a chain of community health centres, which were forerunners of community-based primary health care. Gluckman became Minister of Health in 1945, but the Nationalist Party assumed power in 1948 before the Gluckman recommendations had been implemented, and they were subsequently rejected.

(Coovadia et al, 2009: 825).

However, current policy and practice does not match this earlier vision. In fact, when the post-apartheid government of national unity came into power in 1994, while this inaugurated a huge proliferation of structural changes towards a more inclusive society, perhaps inevitably there were some unintended consequences. This included a focus of curative services (the AIDS epidemic also being a factor) and health authorities let prevention go (Coovadia et al, 2009). As Maylene put it, it was very easy to stop or neglect child health surveillance and promotion, but VERY hard to re-establish it.

Community health worker roles were developed, but with ‘little standardisation of the roles of the healthcare workers, or in their training and supervision… [often] …[f]ocusing solely on tasks related to their diseases of focus’ (Coovadia et al, 2009: 830).

According to Maylene, such workers are not equipped for primary preventive child and family public health. The adoption of the First 1000 days strategy uses a ‘Survive, Thrive and Transform’ framework for analysis and action. While ‘survive’ is essential, the strategy clearly seeks to energise ‘thrive’ and ‘transform’, and in this context the UK’s universal primary preventative health visiting model has obvious appeal.

Launch event at Khanyisa Community Church – hope, help and healing

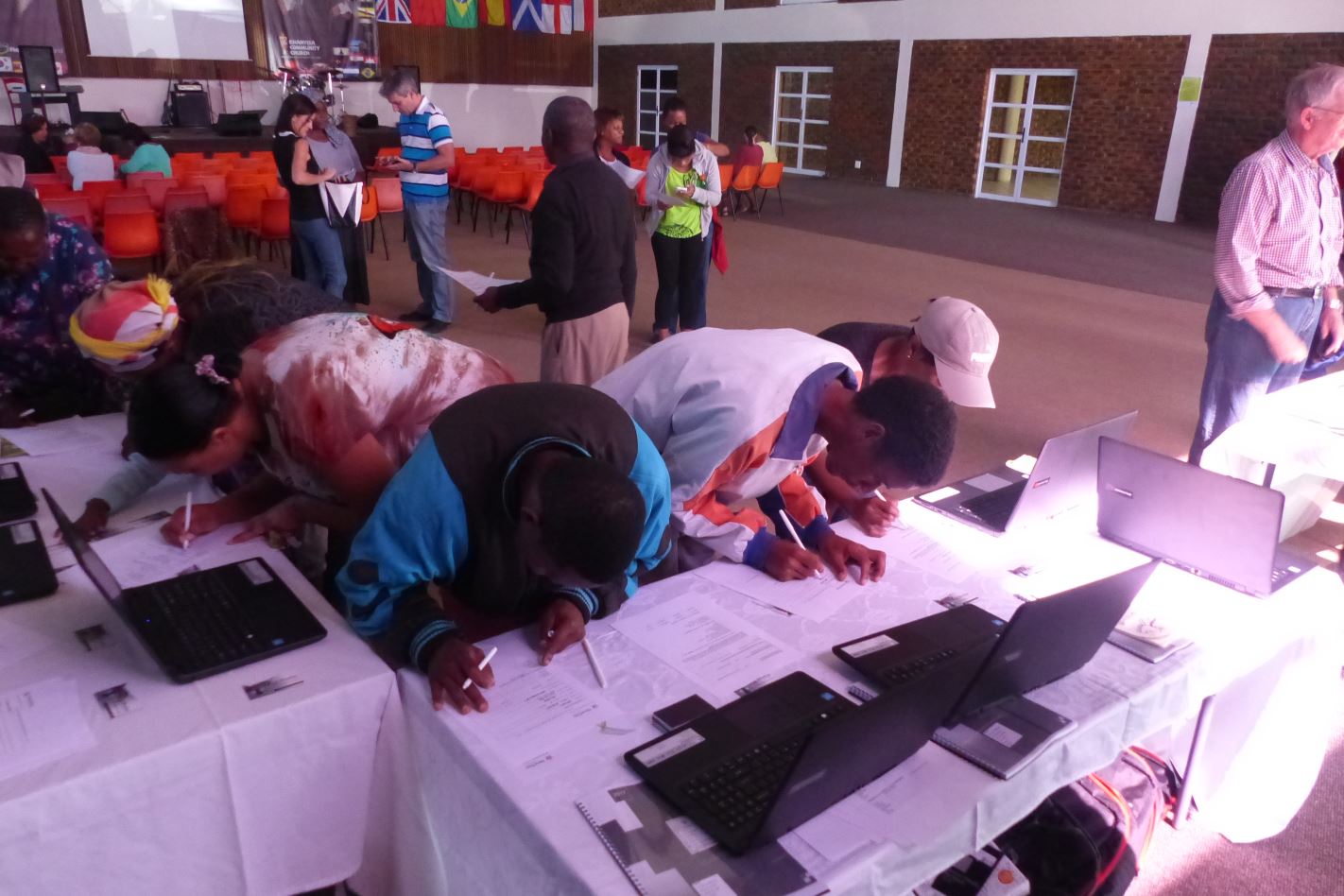

The phrase ‘hope, help and healing’ is a phrase coined and repeated by the NGO NewDay United which has provided me with hospitality and facilitated many connections in South Africa. On Saturday, I joined a launch event at Khanyisa Community Church, that was the outcome of a NewDay workshop a year earlier to share dreams.

Early morning sandwich making for launch and celebration of community initiatives for ‘hope, help and healing’ at Khanyisa Community Church.

This event celebrated the launch of a homework club, and community kitchen, peer-mentoring in school and a computer learning centre. If this were not impressive enough, this comes from a community where many could be described as the poorest of the poor. The lady, who runs the homework club, lives with her daughter in what we might regard as a shack and presently has no paid work. And across the street there were three gang-related shootings this week.

Last week, I mentioned ‘collective leadership’, and this week has manifested not its absence but its necessity in the most challenging of situations. Moreover, it has taught me (again) that community capacity building is NOT an optional luxury, but a practical necessity; and primary prevention is a precious asset that is foundational to healthy lives and longer term outcomes. Transformation is an over-used word, but at today’s launch event it was evident.

Next week, I’ll be meeting with another community-based church developing their own First 1000 days approach…

Reference

Coovadia et al, (2009) The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. The Lancet Vol 374 September 5, 2009: 817–34.

Robert Nettleton